In the Christian tradition, solitude is often spoken of as a gift or a discipline. Loneliness, by contrast, is usually named as a wound. However in reality the boundary between the two can be blurred, especially when aloneness is not chosen but imposed.

For many people, being alone has never felt safe or spacious. For some, solitude intensifies anxiety, trauma, or a sense of abandonment. That matters, and it needs saying clearly: solitude is not a universal good, and it is not a discipline everyone can or should practise in the same way.

And yet, for some of us, solitude emerges not as a spiritual ideal but as something learned early out of necessity rather than desire.

Growing up in a context of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), I learnt early how to be alone. Often this was about safety: stepping away from noise, volatility, or emotional unpredictability. Nature became a place of refuge fields, woods, and in particular streams. These were places where my body could settle and my breathing could slow.

At the time, I didn’t have the language of spirituality. But I did have a fragile awareness that there was something more going on than mere escape. Being alone in nature carried a sense of depth, even if I couldn’t name it as prayer. It might have been hope, or longing, or even wishful thinking. But it felt like more than emptiness.

Looking back, I recognise that this awareness resonated so much with my current understanding of the Beloved and a deeply ecological spirituality. Long before belief is articulated, creation bears witness. The Christian tradition has always held that God is not only encountered in words and doctrines, but in presence, stillness, nature and attentiveness.

Loneliness and solitude are not the same

Loneliness is being alone without meaning, without connection, without a sense of being held. It contracts and restricts our sense of self. It corrodes trust. It can be spiritually dangerous, especially when wrapped in religious language that praises endurance but ignores pain.

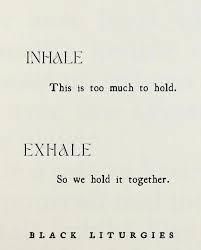

Solitude, by contrast, is aloneness with attention. It may not always be chosen at first, but it becomes formative when it is accompanied by awareness of G-d, self, others and creation. The difference is not the absence of people, but the presence of a broader more connected relationship. Jesus himself embodies this distinction.

Over time, what began as survival slowly became something more intentional. Solitude developed into a discipline that I recognised from within. It became a place of presence without needing to perform competence, leadership, or certainty.

But still my ACE shape how Solitude now functions. On a good day solitude acts as a :

- resistance to urgency,

- resistance to the pressure to be endlessly available,

- resistance to the belief that my value is measured by visibility or output

- A reminder that God’s work does not depend on my exhaustion.

- A reorientation back to ministry flowing from being held, not from holding everything together.

On a bad day muscle memory takes over and I run for the hills or curl up in a ball beside a stream or focus on a tree….but that’s also ok. Too often however it means a withdrawal from connections that I should be paying attention to and that’s not ok.

I’m aware that my story cannot, and should not, be universalised. For some, solitude needs to be approached gently, or not at all. For others, healing comes first through community, therapy, structure, or safety. The Church does harm when it spiritualises isolation or confuses withdrawal with holiness.

The tentative testimony of my own life, my experiences of needing to be alone, held within nature and accompanied by an early, imperfect sense of “something bigger” became the soil in which a discipline of solitude could grow. What once protected me has become something that now strengthens me.

And perhaps that is one of the quiet redemptions at the heart of Christian formation: that God meets us not only in what we choose, but also in what we survive and patiently teaches us how to dwell there with hope.